Three years ago, we set out to apply the decentralization ethos to the power grid — a complex, sprawling network with some parts dating back over a century. That was the beginning of the Decentralized Energy Project, an effort within AbstractionLab. Now that the Filecoin network is running, we are wrapping up our work on the broader grid and focusing our energy-related efforts on Filecoin itself – more on that soon! For now, we invite you to join us on a tour of our power systems project: its achievements, pivots, and our thoughts on its future.

Origins

PL was founded with a vision – not just to develop a specific set of technologies, but to drive humanity forward by tackling ambitious computing problems requiring a broad research and development pipeline. Much of what we do as an organization lies at the late-stage implementation end of that development pipeline and has immediate relevance to the direction and day-to-day operations of Protocol Labs. But many of our projects reach maturity over a longer time period. These longer-arc projects often begin with an element of inherent uncertainty: step one of the plan is to create new knowledge in order to determine the next phase of the plan itself.

A key part of doing this successfully is dividing the pipeline between research, development, and production phases and managing each appropriately. Organizations that get good at pushing ideas along these phases develop frameworks for describing and triaging that process. Examples are basic research, applied research, and development at Bell Labs and the Technology Readiness Levels used by DARPA and NASA. A new idea, inchoate at the early stage of that pipeline, is progressively validated as it passes through. At each stage, a decision is made whether to commit more resources to pursue the project as it is derisked and further developed.

At PL, Abstraction Lab (formerly Independent Research) pursues problems at the earliest stages of that R&D pipeline. Our job is to look broadly at PL — both the direction of the organization itself and its global context — and to find leverage points where some new piece of knowledge or technology could improve our future trajectory.

PL Research recognizes that energy is one of these leverage points. We live today in the context of more violent hurricanes, orange skies in California due to wildfires, deadly snowstorms in Texas, the increased spread of fatal mosquito-borne viruses, flooding in coastal cities, and species extinction rates that are high on even geologic timescales. These problems are driven by a changing climate, which is tied to the global energy system. Energy use in turn is dominated by three flows: oil used for transportation, natural gas used in buildings and industry, and electricity. All of these flows are maintained by giant organizations possessing extended supply chains and huge amounts of infrastructure under centralized control. Decentralizing the energy system is both aligned with the Web3 ethos and key to environmental sustainability.

A first-principles view makes the possibility of decentralizing the energy system clear:

-

The US uses about 100 quads of energy in a year, or about 3.3x10$^{12}$W of power.

-

An estimate of solar irradiance (the solar power that reaches the ground) is 1000 W/${m^2}$. Estimating a solar cell efficiency of 24% and an average of 6 hours per day of sunlight at this irradiance level gives us 60W/${m^2}$ of practical energy production per area of solar cell. (This efficiency is at the high end for current mass-market solar but is very achievable)

-

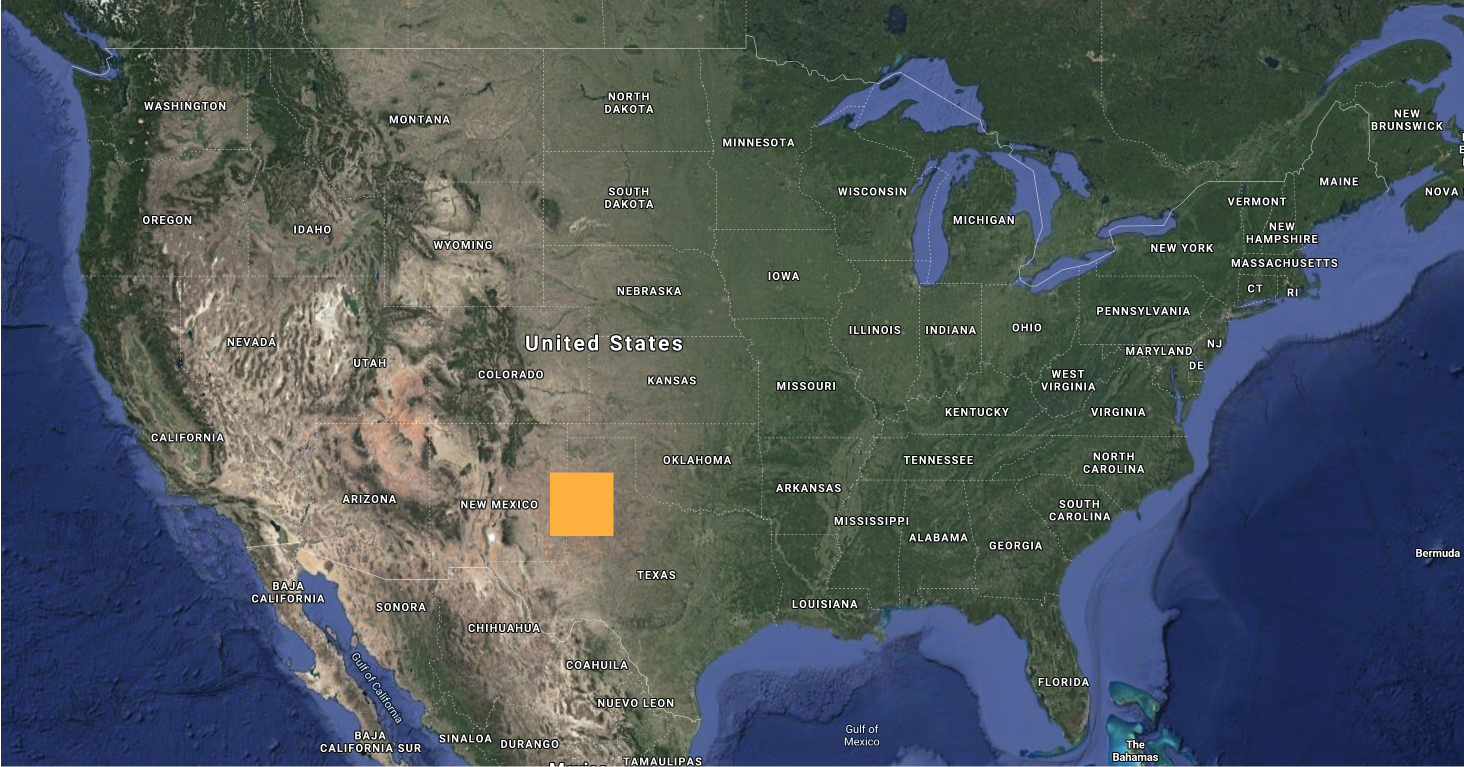

This means that to power the entire country with solar energy, we’d need an area of land about 147 miles on a side (as shown in figure 1).

Figure 1: To power the entire United States with solar power would require a square about 147 miles on a side. This includes energy from all sources: not just electricity, but the energy used in transportation, industry and heating buildings.

The lesson from this is that our planet’s solar resources are huge compared to the amount of energy we consume. And because sunlight falls everywhere, green energy production doesn’t need to be centralized. With the electrification of fuel-dependent energy uses such as heating and transportation, there will be much less need for environmentally damaging centralized supply chains aimed at recovering, processing, and transporting natural gas and oil. In a direct parallel to the vision of the world embraced by IPFS and Filecoin — in which large, centralized data centers are replaced by a distributed network of miners and collaborating nodes — it is possible to make our society vastly more sustainable by producing energy closer to where it is consumed.

Decentralizing the Power Grid

Today’s power system is built to transport electricity from a small number of large-scale generating facilities to a large number of customers. It is designed this way because historically, large-scale generation was both cheaper due to economies of scale and easier to control. This ease of control was necessary because the power grid has very little storage: the energy consumed by customers must closely match the energy injected into the grid by generators on a second-to-second basis. When the basic architecture of the power system was designed during the beginning and middle of the twentieth century, there were no communications systems that could feasibly coordinate distributed generation with distributed demand. As a result, the guarantee of reliability in the legacy power system rests on a foundation of centralized control and top-down engineering. Changing the basic assumptions underlying this architecture is necessary for achieving a decentralized grid, and requires redesigning power system controls to achieve coordination without centralization.

Complicating the picture is that power systems are spread out among many overlapping jurisdictions and consist of expensive infrastructure which is replaced only infrequently. Upgrading the centralized control system with a decentralized system all at once is impractical: any new system will need to be interoperable with the legacy grid and accommodate a patchwork of incremental upgrades.

Approaching this problem from a distributed systems perspective, we asked what control architecture would best allow an evolution from a centralized grid to a decentralized grid? What would enable a patchwork of upgrades, while maintaining system reliability and security? How can the grid be ‘future-proofed’ so that investments today are compatible with future innovations in controls systems? And what technical expertise can we contribute, as an organization with experience building decentralized systems for information storage and retrieval?

A Functionally Defined Invariant Architecture

A key barrier to decentralizing the power system is its complexity, which makes the system difficult to modify without unintended consequences. Today’s power system “works in practice but not in theory,” the result of a succession of interrelated engineering projects built on top of one another over the past century. Decentralizing regions of the power system while allowing interoperability with the legacy grid requires a strategy for managing the complexity of the system as it is modified.

System design affects how complexity evolves as the system is modified, and thus how future-proof the system is. Engineers often design simple, elegant modules that perform a task efficiently according to the current process design iteration. One drawback to this approach is that simple modules tend to expose complexity at the interfaces representing information flow between modules. By contrast, “deep” modules which present simple interfaces relative to their underlying implementations provide a backstop for comprehensibility. Deep modules allow overall system behavior to be explained by reference to the simple interfaces and high-level functions of each module. Another problem with designing simple, shallow modules is that this tends to codify features of the most recent design in a flowchart-like architecture. Such an architecture is not robust to design changes. A future-proof system should therefore both compartmentalize complexity in deep modules and cordon off the design decisions most likely to change in the future.

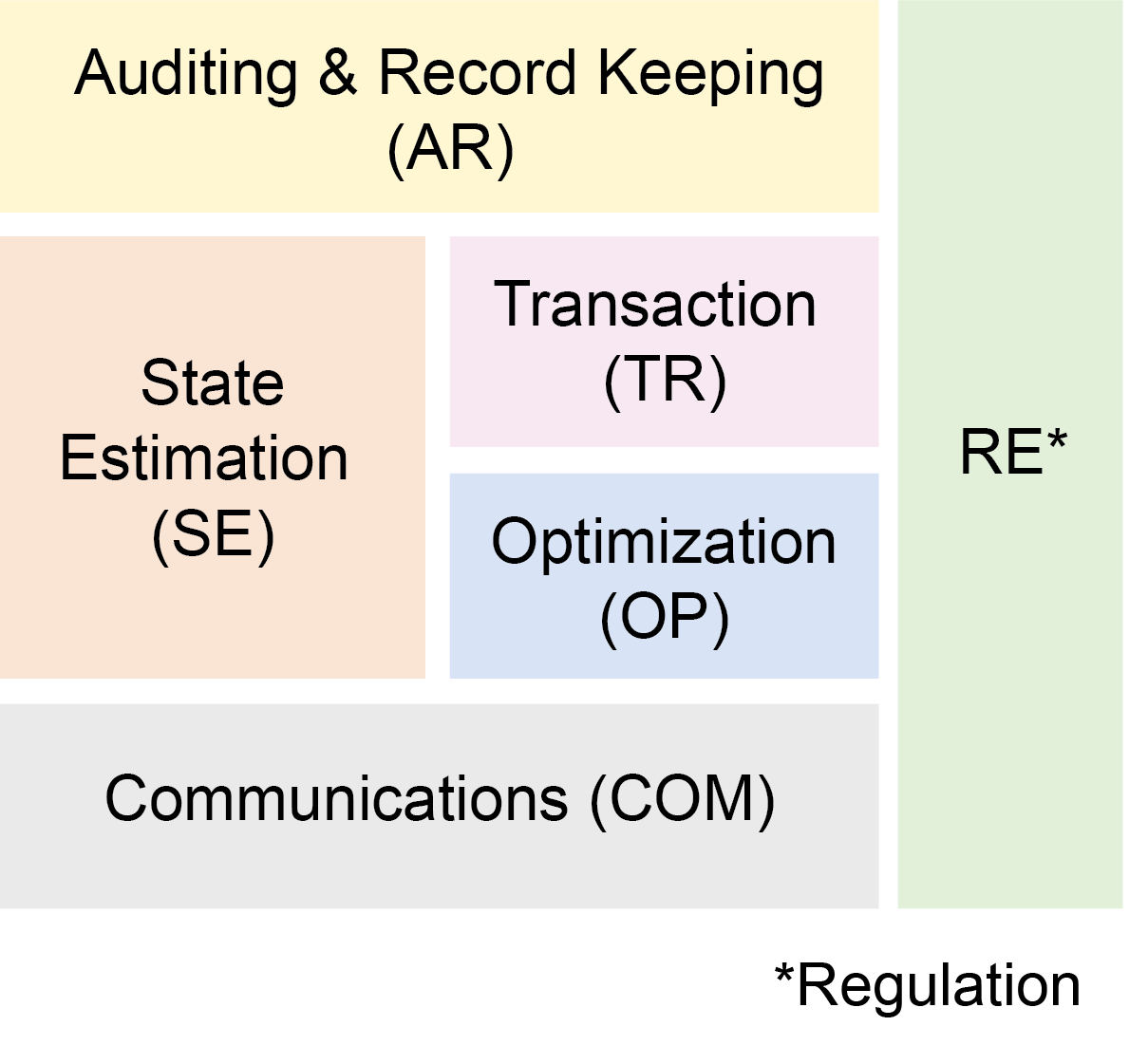

Applying this thinking to power systems, we developed a “Functionally Defined Invariant Architecture” (FDIA) for the power grid (Figure 2). The FDIA breaks the overall power system into fundamental tasks needed for grid operation. For example, separating transactions from other tasks in principle allows a grid operator to implement a digital payment system without substantially affecting other operations. These tasks are deep modules with simple interfaces between them, that thus allow upgrades while minimizing increases in complexity of the overall system.

For more on the FDIA architecture and how it enables the transition to a distributed power system, see our previous post and publications below.

Figure 2: Functionally Defined Invariant Architecture (FDIA) for the power grid.

Agent-Based Modeling

The deep modules of the FDIA aim to codify processes that all power systems must perform, in order to accommodate changes without requiring architectural modifications. Because interfaces within an FDIA are standardized, modules can be upgraded without disrupting the architecture. The FDIA’s standardized interfaces allow a heterogeneous mixture of nodes to exist within a power system.

To test these ideas, we wanted to build hierarchical agent-based systems in which an FDIA controls both a local distribution system and individual nodes in that system. Here, tasks such as internal optimization are handled within a node and the communications modules of each node receive price signals from the distribution system FDIA. A separation of concerns is maintained between each module.

We build these agent-based systems using VOLTTRON, an open-source, multi-agent sensing and control platform for microgrids developed by Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL). In addition to being used in research, VOLTTRON is used as an energy management system in the field: for example, by Washington DC’s Department of General Services. Estimates as of 2019 suggest that VOLTTRON’s usage in more than 60 DC buildings saved the city $1.5 million per year in energy costs.

We modeled individual FDIA modules as agents communicating over a VOLTTRON message bus, and ran simulations using IEEE feeder data. These tests demonstrate that by using an FDIA architecture, it is possible for subsections of the grid using decentralized power management systems to coexist with systems based on a centralized architecture. This establishes a feasible pathway for transitioning to a fully decentralized power grid.

For more information about this work, see Michael’s TESC 2020 Presentation and our publications below.

Formally Verifying Grid Systems

In August 2003, there was a localized outage in the power grid near Akron, Ohio. FirstEnergy, the local grid operator, would normally respond to an outage by adjusting generation and rerouting power. In this particular case, operators were unaware of the problem due to a bug in the software they were using to monitor the system. They even ignored calls alerting them to problems because their system showed no error. The result was a cascade that rippled through the Northeastern electric grid, causing an outage that affected 45 million people.

The XA/21 Energy Management System with the error had not only undergone normal testing by its developer, GE Energy, but had been run for over 3 million operational hours without the bug being noticed. The error was a rare race condition in which two processes competed to write to the same location. Similar subtle bugs are common in distributed systems, and are difficult to detect during a normal design and testing process. Compounding the risks as the power system is decentralized are cybersecurity concerns. Historically, critical grid infrastructure has been air-gapped from the internet. An increasingly networked power grid — and particularly, one in which distributed generation such as home solar plays a significant role — has a vastly expanded attack surface.

The third part of our work was therefore to formally verify control systems for distributed power grids. Formal verification tools, such as model checking using TLA+, exhaustively survey system states in order to find errors that would be difficult or impossible to detect using normal testing. They bring rigor to system design and increase confidence that the system will actually work as intended.

We developed a series of TLA+ models to formally verify an FDIA-based control system using test feeder data from IEEE. In doing so, we proved a path forward for upgrading the grid as a network of distributed power systems without sacrificing reliability or security.

Figure 3: Animation showing satellite photos of the Northeastern US before and during the 2003 blackout. Maybe GE should have used a ‘test, but verify’ approach… ( Public domain )

Next Steps

According to the pipeline model discussed above, there comes a time when basic research on a topic ends and a decision must be made about whether to translate the work into an applied project.

Having completed research establishing a new framework for distributed energy controls systems, exploring interactions between these systems with agent-based models, and formally verifying system behavior, it became clear to us that we are entering a new phase in our energy research efforts. Taking the next step in developing this line of decentralized-power-systems-related work would require scaling up the engineering and policy elements of this project. For now, we’re putting that on hold while we apply our insights to exploring the Filecoin network itself: both analyzing its energy use and looking at how to optimize it to encourage low- and zero-emissions mining.

That said, we are excited about the future of distributed power systems and are interested in supporting further work in this area. If you have ideas for building on this work or pursuing related projects and would like to discuss them, please reach out!

Reports, talks, code and peer-reviewed publications from this project:

- Ransil, Alan. Energy Pricing. Protocol Labs Research Report. (2018)

- Ransil, Alan. Microgrids. Protocol Labs Research Report. (2018)

- Ransil, Alan. Price signals and demand-side management in the electric distribution and retail system. Protocol Labs Research Report. (2018)

- Hammersley, Michael. Electricity Policy and Market Design. Protocol Labs Research Report. (2018)

- Ransil, Alan. A Multilayer Power System Model for Future-Proof Interoperability. MIT Energy Initiative Electric Power Systems Center Workshop. (2018)

- Hammersley, Michael. Smart Grid Pilot Projects. Protocol Labs Research Report. (2018)

- Ransil, Alan. Fonkwe Fongang, Edwin. Hammersley, Michael. Celanovic, Ivan. O’Sullivan, Francis. A computable multilayer system stack for future-proof interoperability. IEEE PES Transactive Energy Systems Conference. (2019)

- Hammersley, Michael. Decentralized Energy Grid: A Protocol Labs Independent Research Project. Protocol Labs Research Seminar. (2020)

- Hammersley, Michael. Ransil, Alan. Hello from the Decentralized Energy Project! Protocol Labs Blog. (2020)

- Hammersley, Michael. Ransil, Alan. O’Sullivan, Francis. Enabling Plug and Play Transactive Energy on Legacy Power Grids. IEEE PES Transactive Energy Systems Conference. (2020)

- Ransil, Alan, Michael Hammersley, and Francis M. O’Sullivan. Improving system resilience through formal verification of transactive energy controls. IEEE PES Transactive Energy Systems Conference. (2020)

- Ransil, Alan. github.com/redransil/TLA-laminar: Release v0.14.0 (Version v0.14.0).Zenodo. http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4162501 (2020)

- Two additional manuscripts in preparation