By now you may have heard about ResNetLab’s research endeavour to drive speed-ups on file transfers: Beyond Swapping Bits. Our recent blog post, “Honey, I shrunk our libp2p streams”, considers how adding compression to libp2p could lead to significant bandwidth savings. An even more recent post, “Two ears, one mouth: how to leverage bitswap chatter for faster transfers”, evaluates how tracking useful information from the normal operation of Bitswap (such as the content requested by neighboring peers) could result in reductions in the time needed to fetch popular content and the number of messages exchanged.

In today’s post, we want to share how adding a TTL (Time To Live) field to Bitswap messages extends Bitswap’s content discovery range. We approached the evaluation of this new scheme the ResNetLab way: from idea, to RFC, to prototype, to results. In this case, our prototype gives IPFS nodes the ability to discover content stored in nodes TTL+1 hops away without having to resort to the DHT, which is not possible using Bitswap’s current implementation. This results in an improvement in the average time-to-fetch of up to 33% above baseline Bitswap with the DHT enabled. The cost we pay for the improvements is a 1.6% increase in the average number of messages exchanged per node and a 5X increase in the number of duplicate blocks traversing the network.

The contribution

The idea for this RFC came not from an academic paper, but rather from this Github issue by the brilliant Alan Shaw. The basic hypothesis was the following: in its current implementation, when Bitswap is not able to find the content it is looking for from its directly connected peers, it resorts to the DHT to find a provider for the content. By adding a TTL to Bitswap messages, nodes are able to forward their request for content to nodes TTL+1 hops away, extending their range of discovery and minimizing their dependence on the DHT (especially if the content requested is not rare).

When a node receives a WANT message with a TTL greater than zero, it reduces the TTL of the request by one and forwards the request to d (degree) of its connected nodes that haven’t yet received this request. All the logic behind the request and discovery of content on behalf of other peers is managed through a special session that we call the relay session. The relay session tracks all the WANT messages and CIDs being requested on behalf of other nodes. When a node receives a block from a request belonging to some other peer, it forwards it to the source, following the same path as the original request (symmetric routing).

In addition to enabling Bitswap to find content without having to resort to the DHT, this implementation also improves the time to fetch content not stored by directly connected peers by 33%, increases the number of messages exchanged by 1.6%, and creates a 5-fold increase in the number of duplicate blocks exchanged in the network.

The methodology

Discussing the RFC and building the prototype

As is standard with every prototype built by ResNetLab, we started with the design of an RFC to discuss the hypothesis and build the foundations for the prototype. With this RFC, we wanted to evaluate how increasing the discovery capabilities of Bitswap without having to resort to the DHT could lead to improvements in content exchange within IPFS. To this end, we added a TTL field to Bitswap messages and gave peers the ability to discover content on behalf of other peers through a relay session.

You can check out the implementation of the RFC in this go-bitswap fork, read a detailed description of the RFC here, and view some calculations we performed to model the prototype here. To summarize, this new addition to the Bitswap protocol works as follows: when client A starts a query in the IPFS network, Bitswap initialises content discovery by adding a TTL to its WANT message requests (TTL=1 by default). When node B receives this request, if it doesn’t store some of the CIDs the peer is requesting, it looks at the TTL of the request. If the TTL is greater than zero, node B notifies its relay session and requests the discovery of these CIDs on behalf of node A, decreasing the TTL by 1.

The relay session of B forwards the request with TTL-1 to d (degree) of its connected peers that haven’t seen that request yet, thereby extending A’s content discovery. If one of B’s connected peers has any of the CIDs being requested by A, B fetches the blocks and forwards them to A. The relay session keeps track of every CID requested on behalf of other peers, so that any block for that CID that is seen can be conveniently forwarded to the requester.

The degree d of the relay session is used to prevent the network from being flooded by forwarded requests. Thus, the performance of the protocol can be conveniently adapted through the configuration of the TTL and the degree of the relay session. Larger TTLs lead to extended ranges for content discovery at the expense of a higher messaging overhead that can be controlled through the degree d.

In the following animation the operation of the protocol with five different nodes is illustrated:

Figure 1: Operation of the protocol with five nodes

Evaluation Plan and Results

The we were trying to evaluate in this RFC is the ability of Bitswap nodes to extend their discovery range to nodes TTL+1 hops away. For the evaluation of the protocol, we designed an experiment where 15 different leecher IPFS nodes requested different types of content from five different seeder IPFS nodes in the network. In the experiment, leecher and seeder nodes are not allowed to be connected directly, and they can only communicate through a set of passive nodes that neither provide nor request content from the network but run the Bitswap protocol normally. For the experiment we used links of 100MB with 100ms latency between nodes, a TTL = 1, and a degree d = 10.

Exchanging small files

First we evaluated the performance of our protocol for the exchange of small files such as this XKCD image of 66 KB.

Figure 2: XKCD image exchanged by nodes in our experiment

We used the vanilla implementation of Bitswap with the DHT enabled and disabled as a baseline, and compared it with our prototype of Bitswap with TTL. For baseline Bitswap with the DHT disabled, every request for content by leechers times out. Leechers broadcast their request for content to their directly connected peers and, as they are only connected to passive nodes which do not provide content, and they can’t resort to the DHT to find a provider for the content, they are unable to find the content they are looking for.

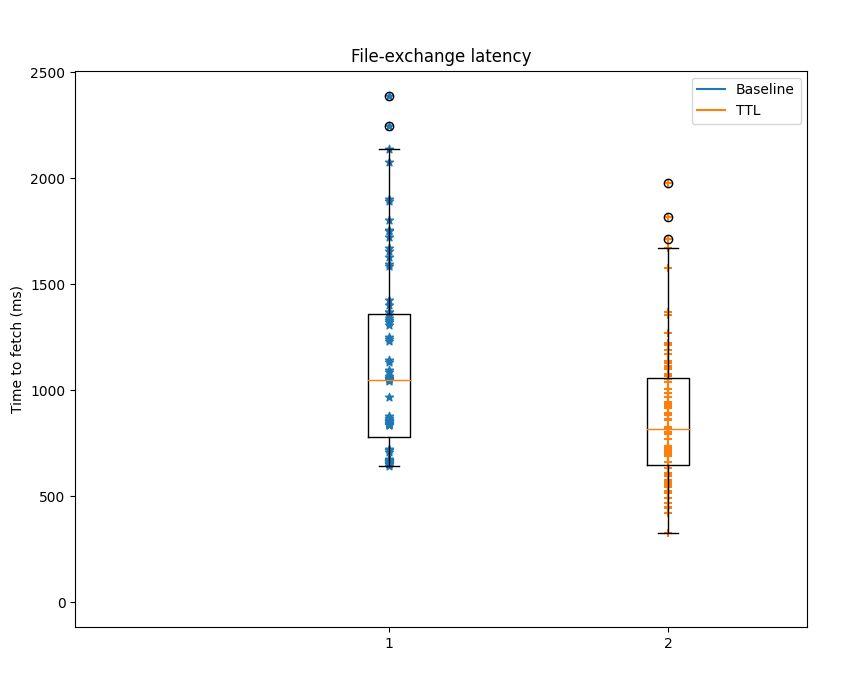

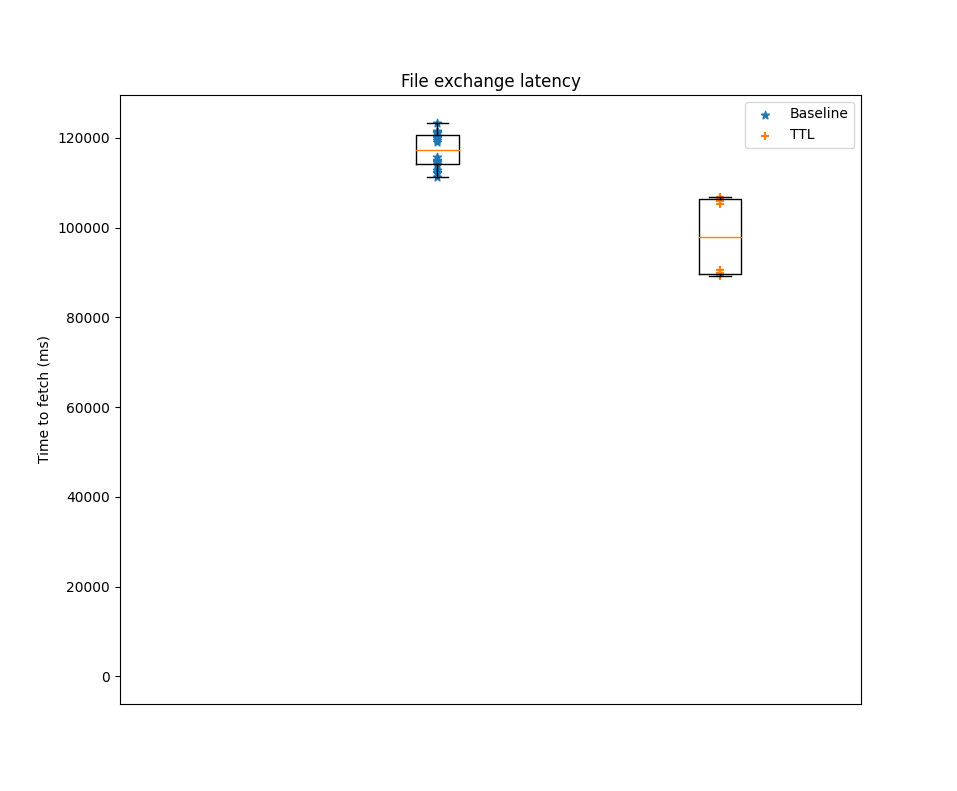

If we enable the DHT in the baseline protocol, leechers are now able to find the content for which they are looking but need to resort to the DHT to find the nodes providing it. By comparison, our RFC’s implementation using TTL in Bitswap messages results in faster discovery and fetch times (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Time to fetch xkcd image

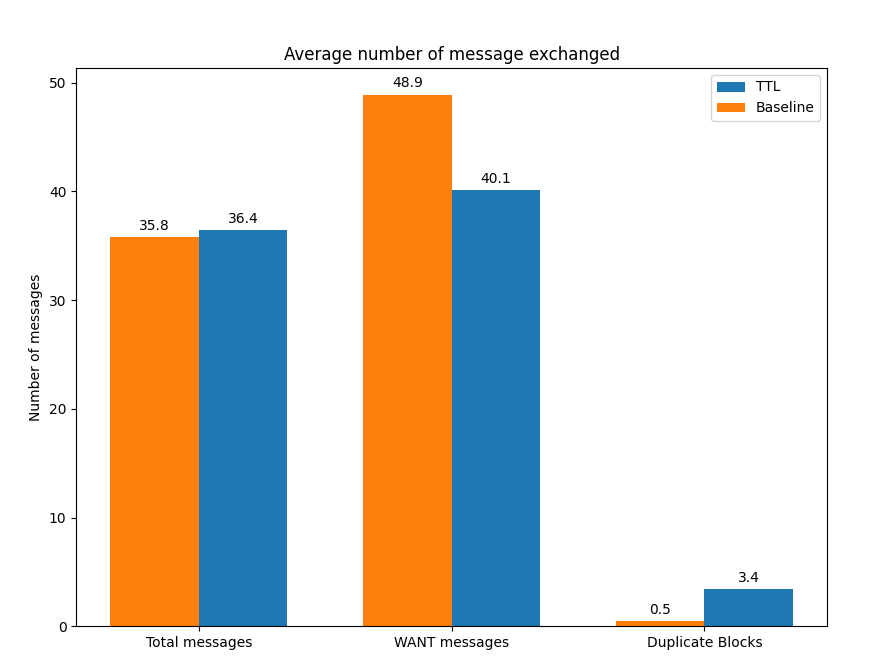

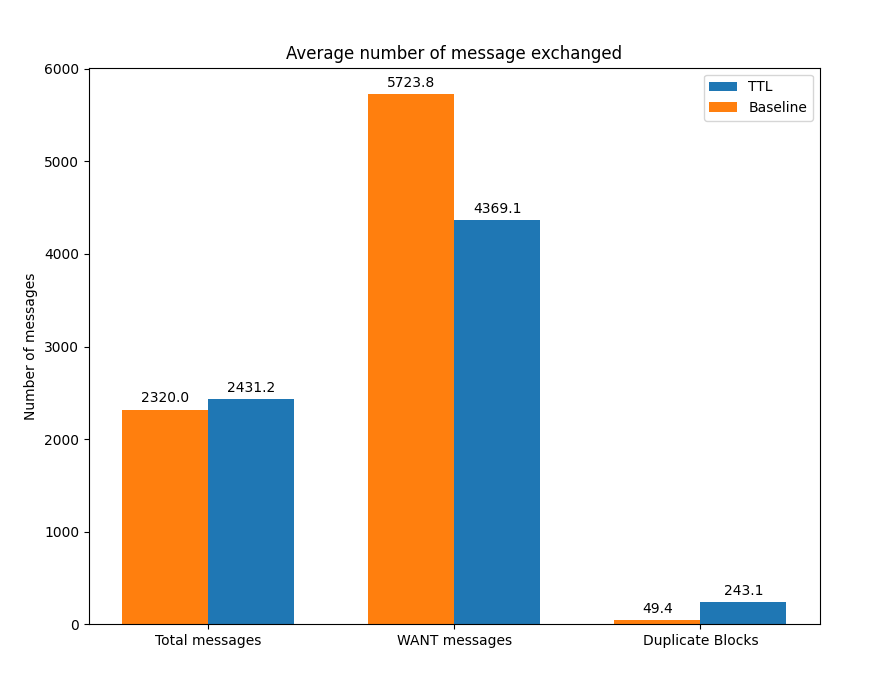

As always, this improvement in content discovery and content fetch time doesn’t come for free. The use of TTL in Bitswap messages results in a message overhead of only 1.6%. Bitswap messages can include several WANT requests in them, thus, the prototype is able to achieve a slight reduction in the number of WANT messages exchanged (Figure 4). The real overhead, however, comes from the number of duplicate blocks exchanged in the network. By delegating the discovery of content to other nodes, we are amplifying the range of the request, but we are also making it more difficult for the requester to notify peers seeking blocks on its behalf when it has received the requested CIDs. Peers that are not able to see the requester’s CANCEL message continue their search, forwarding the blocks that have already been fetched. This results in the appearance of additional duplicate blocks.

Figure 4: Number of messages exchanged for XKCD image exchange

Impact on larger files

The results for the xkcd images were promising: this scheme gave nodes the ability to find content some hops apart without having to resort to the DHT, even achieving faster times-to-fetch than when using the DHT. Would this result hold for larger files? We repeated the same exact experiment from above with a 30 MB file, and we obtained the results depicted below:

Figure 5: Time to fetch 30MB file

We can see in Figure 5 that the time to fetch the file for the TTL prototype is improved 17% on average compared to the baseline implementation of Bitswap with the DHT enabled. Unfortunately, the cost we pay for this is an increase of up to 4 times the number of duplicate blocks in the network relative to the baseline experiment (Figure 6). Again, the fact that nodes don’t have an easy way of cancelling relay sessions started by other peers on their behalf is causing an increase in the number of duplicate blocks.

Figure 6: Number of messages exchanged for XKCD image exchange

Large scale networks

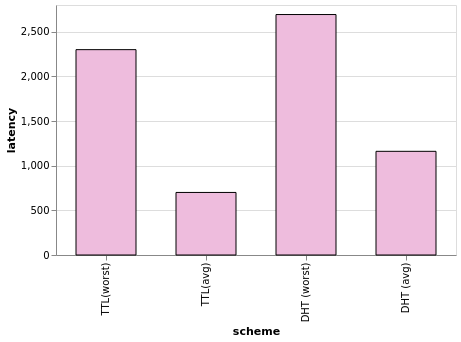

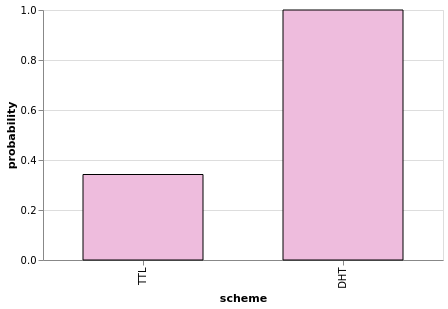

Now we understand the potential of the RFC in a network with a few dozen nodes. But what can be the expected impact of this TTL approach in a large scale network deployment? To evaluate this, we prepared an ObservableHQ notebook with back-of-the-envelope calculations to help us understand the behavior of the protocol when compared to the DHT on a large scale.

In this notebook, you will be able to play with a lot of configuration parameters for the DHT, the TTL protocol, the network, and the popularity of the content to get an approximate comparison between the DHT and our “jumping Bitswap” protocol when it comes to latency and the probability of finding content.

Figure 8: Sample latency plot from the Observable notebook

Figure 9: Sample plot from the Observable notebook depicting probability of finding content

Conclusions and Future Work

The implementation of this RFC opens the door to a new field of exploration: the design and use of alternative protocols that don’t rely on the DHT for the discovery of content. In this case, we simply added a TTL field to Bitswap messages in order to increase the range of discovery by partially flooding the network, but we are already devising new ways to perform smarter discoveries without having to rely exclusively on DHT lookups. The goal is to achieve ever-faster and more efficient exchanges according to the state of the network and the content being retrieved.

In the meantime, we are working on several improvements to our current implementation of the “jumping Bitswap” alternative:

-

First, we need to implement a way for nodes to notify peers looking for CIDs on their behalf that they have already received the sought-after block. This will minimize the number of duplicate blocks in the network, making a more efficient use of bandwidth. A good first approach would be to use asymmetric routing for the forwarding of blocks (instead of the current symmetric routing). In the asymmetric routing approach, WANT messages would include a “source” field along with the TTL field. Peers would include their PeerID as source in the WANT messages so that when the requested block for a relay session is found, instead of being forwarded following the same path followed by the WANT message, it can be directly sent to the requester without traversing intermediate nodes. This extension to the protocol would reduce the bandwidth use compared to the current prototype, at the expense of requiring an opened connection between the peer storing the block and the requester. This introduces new limitations such as the additional delay in the exchange of content due to this connection opening, and the fact that in certain cases the requestor may not be directly dialable.

-

Even more, we can build on the WANT inspection RFC we recently implemented and shared in this blog post. One of the interesting results of this RFC was a reduction in the number of duplicate blocks. Instead of broadcasting WANT-HAVEs to every connected peer, nodes in this RFC inspected WANT messages from neighboring peers and started their discovery process by directing their search to peers that have recently requested the CID. Populating the peer-block registry with information from nodes up to TTL+1 nodes apart and using this information in relay sessions could lead to making more efficient discoveries, reducing the number of duplicate blocks, and potentially minimizing the number of messages exchanged.

-

Our prototype could also benefit from the use of compression. The use of a TTL in Bitswap requests makes the protocol slightly more bandwidth-inefficient than its current implementation. Using compression over the protocol may offset the bandwidth overhead that results from increasing Bitswap’s range.

-

Finally, in our prototype, Bitswap nodes leverage connected peers to broadcast their WANT messages and flood the network. This forces Bitswap to include mechanisms like degree (d, mentioned above), limit the accepted TTL range, or assign a budget limiting the number of messages that will be processed from any given peer, which prevents nodes from abusing the protocol and mitigates potential attacks. Fortunately, we already have an overlay infrastructure with all these mechanisms in place: GossipSub. An additional future line of exploration to extend this prototype would be to leverage the use of GossipSub to spread WANT messages to other nodes in the network.

There is a lot of exciting work ahead in our quest to make file-sharing on P2P networks blazing fast. Do not hesitate to reach out and join us in this endeavor!