As part of ResNetLab’s research endeavour to drive speed-ups on file transfers, Beyond Swapping Bits, we present a new contribution to IPFS Bitswap protocol. We argue that Bitswap is currently discarding a wealth of information that could be used to its benefit, improving retrieval success and minimizing the latency to retrieve content. You can also read our last contribution here, which targeted compression of libp2p streams.

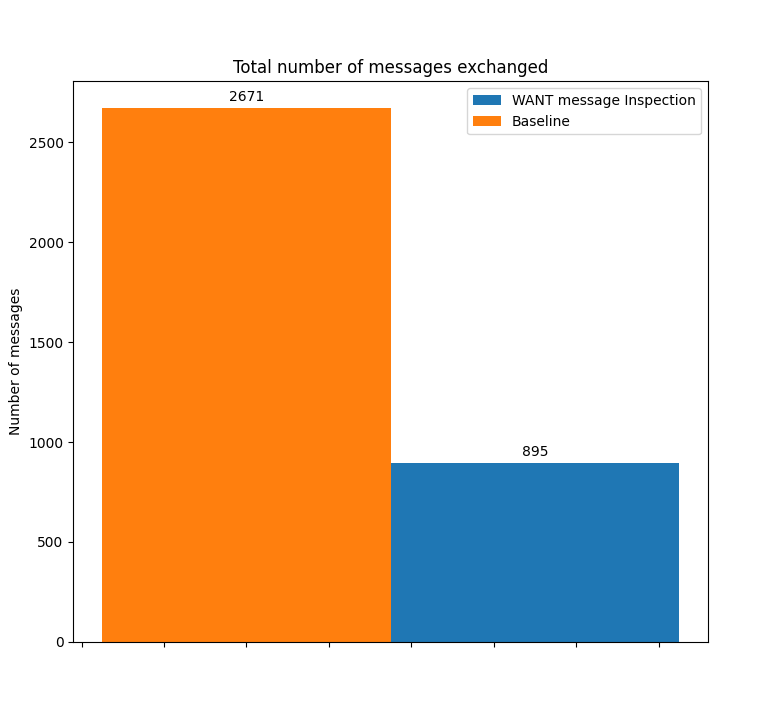

Every research endeavour starts with a thorough analysis of the state of the art. This initial effort builds the foundation for the work to come. What we are doing differently to drive file-transfer speedups in P2P networks at ResNetLab is that beyond giving you the results and how to benefit from them, we want to guide you through the process we followed to reach these improvements, from the state-of-the-art, through ideation and prototyping, to evaluation. We want to illustrate this process by documenting how we prototyped and evaluated the first upgrade, which produced an approximately 25% improvement in the time to fetch popular content, and a reduction of the number of control messages exchanged in Bitswap by 75%. In other words, come for the results, stay for the scientific methodology and the repeatability of the evaluation, so that you can learn how to implement your own variations!

The contribution

IPFS’s Bitswap protocol currently discards a lot of useful information from its connected peers, such as the blocks that those peers are looking for. Our hypothesis was that if we used that discarded information to inform ourselves about the state of the network, we would be able to perform faster content discoveries and, consequently, reduce transfer time.

By keeping the intel about what blocks are being requested by which peer in a new data structure (which we introduce here and we call the peer-block registry), we are now able to guess with high accuracy which nodes have which content. The assumption is that if a node was looking for something, it probably found it.

The peer-block registry is populated with data extracted from the WANT messages received by a peer. With this technique, we can see faster deliveries, especially in cases where content gets increasingly popular over time.

Additionally, we were able to minimize the overhead of bitswap messages. We modified the Bitswap first turn flood mechanism to only send WANT message to the peers we believe to have the CID, if we happen to have any. Given our assumption, the recipient of the WANT message will have the content and immediately transfers the corresponding block, saving precious bandwidth from all the other nodes. If, on the other hand, the node doesn’t have the content anymore, Bitswap falls back to its normal operation (broadcasting WANT messages until a provider with the content is found).

This new scheme showed promising results, reducing by one RTT the time required to discover and transfer popular content (previously requested by other nodes in the network), and reducing the amount of messages exchanged in the network by up to 75%.

The methodology

Building our understanding and identifying limitations

We first performed a thorough analysis of what was being done around file-sharing in P2P networks in previous academic work. We then evaluated the current bottlenecks and limitations of an existing content exchange protocol over an existing P2P network: in our case Bitswap and IPFS, respectively. You can find our notebook on the beyond-bitswap folder at the ResNetLab repo.

We identified that the content discovery perfomed by Bitswap is suboptimal, blind and deterministic. When a file is requested, Bitswap performs a DHT content routing query and sends an optimistic WANT message to all of its connected peers. No information of previous events that took place in the network is used to intelligently guide this discovery.

We knew that we could do better. We hypothesized that we could use some information from the network to make more informed decisions and improve the efficiency of content discovery. Later, we came across this tangentially related paper in which the authors suggest the inspection of requests from peers to identify nodes which underreport the stored content (i.e. that intentionally do not announce pieces of content they store). This simple concept inspired the RFC that we prototyped and evaluated, and that led to our first improvements over file-sharing in IPFS.

Nodes in the aforementioned paper listen to requests to detect underreporting peers; we can use this same principle to track Bitswap’s WANT messages from our peers. This way, whenever we want content that others have requested before, instead of polling the full network from scratch, we first ask nodes that have previously requested that CID, as they will likely have the content.

Crafting the RFC and the prototype

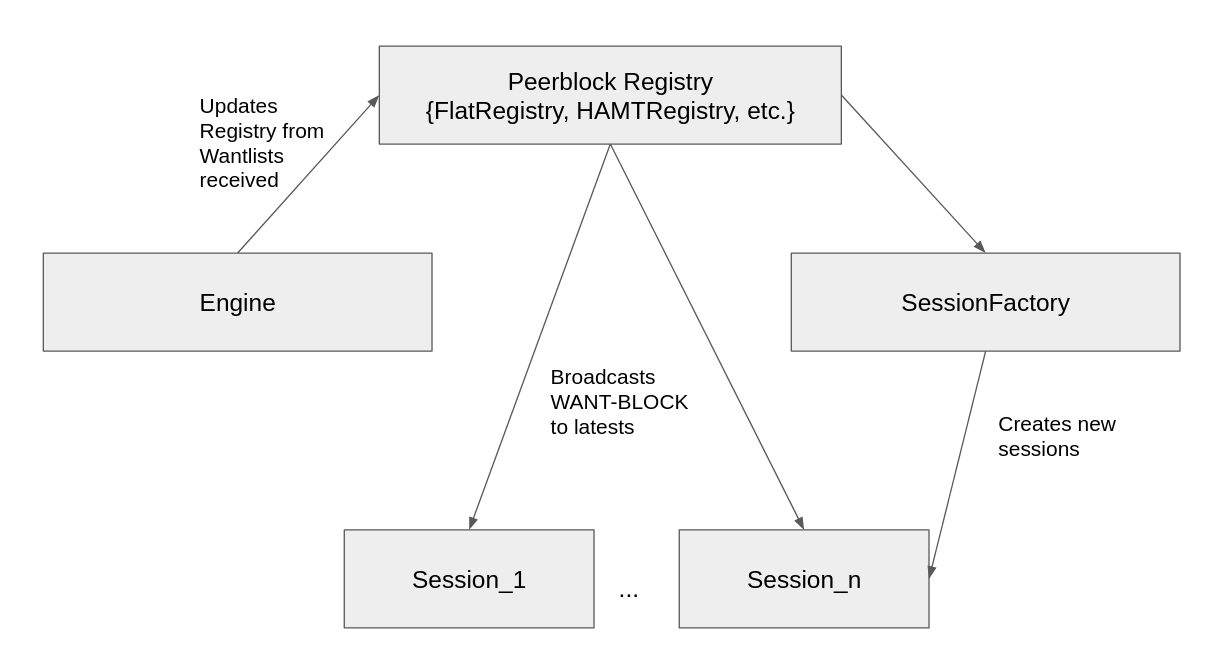

We have drafted an RFC BBL104 so that anyone can can contribute both to the design and evaluation plan of the improvement proposal. To build the prototype, we forked go-bitswap and applied the necessary changes. You can read the details of its architecture in the RFC. The summary is:

- Bitswap tracks every WANT message received and updates a peer-block registry, which is a brand new data structure introduced in this RFC and prototyped for evaluation. The peer-block registry maps each CID seen by a node to the peers that have recently requested this particular CID.

- This information is then used by Bitswap sessions to direct their search for content. Whenever a peer wants a CID, if the peer-block registry for that CID is populated with peers that already requested that content, instead of broadcasting WANT-HAVE messages to all its connected peers, it will only send a WANT-BLOCK to the n latest peers (n=3 in the default implementation) of the peer-block registry.

- If the contacted peers have the content, they will immediately respond the WANT-BLOCK with the corresponding block, while if this is not the case, they will answer with a DONT_HAVE, and the peer will then perform the broadcasting of WANT_HAVEs to all its connected peers.

The expected impact of this scheme is the following: the time to first block (i.e. time to first byte - TTFB) will be reduced from at least two RTTs to one: if the WANT_BLOCK hits a peer with the content it will directly answer with the content, while the penalization from not hitting a peer with content will be of just one RTT.

Evaluation Plan and Results

Our target use case was the transfer of datasets that grow in popularity over time. We designed an experiment where 30 different leecher IPFS nodes request, over time, the XKCD image below (size 49 KB) from a single seeder IPFS node providing it in the network.

To emulate the request of popular content, leechers periodically request the content in waves of size 2, in intervals of 5 seconds. This creates a situation in which the next set of leechers has already received the WANT messages from previous leechers, and can therefore assume that those nodes have the file they were looking for.

Results with standard Bitswap

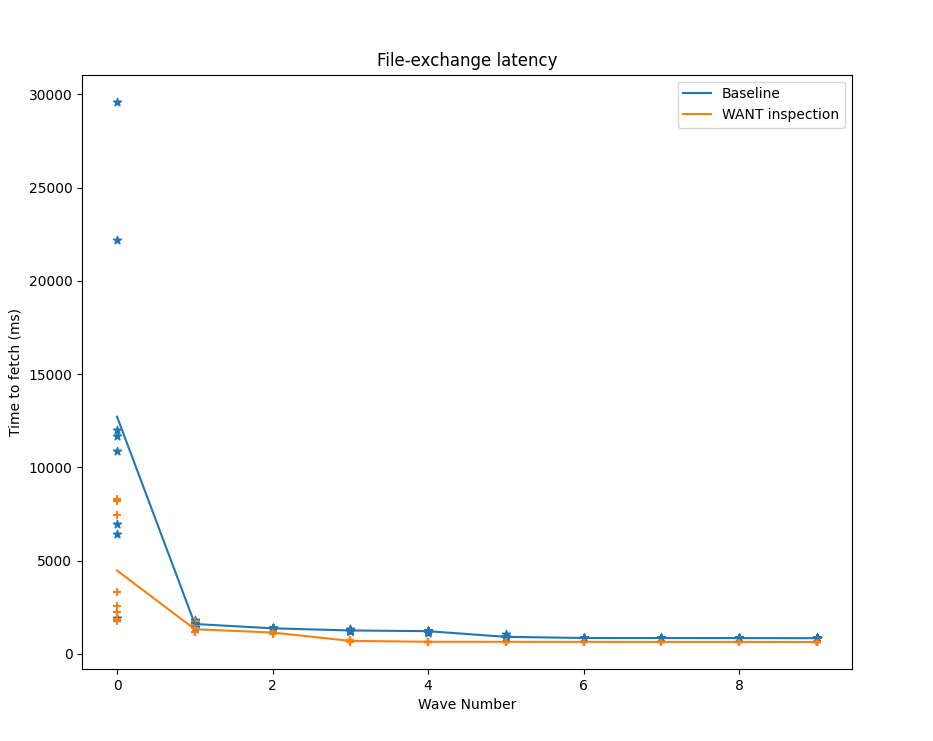

For the baseline implementation of Bitswap, the first retrieval is the slowest because only the seeder has the content. For the following waves, multiple nodes in addition to the original seeder already have the content, so when leechers broadcast their WANT-HAVEs they have a higher probability of hitting a node with the requested content.

Despite hitting a node with the content, the minimum number of RTTs required by the vanilla implementation of Bitswap to get the content is two: one for the WANT-HAVE broadcast, and another one to explicitly request the content with a WANT-BLOCK.

Results with peer-block registry enabled on Bitswap

For our modified implementation of Bitswap with the WANT message inspection mechanism, the time-to-fetch, and thus the time-to-first-block for popular content, can be significantly reduced. Why is this?

As was the case for the baseline experiment, the first wave of leechers has no previous knowledge about where the content is, so the only thing they can do is broadcast WANT-HAVEs, find the seeder, and request the content. For subsequent waves, however, peers have been listening to the WANT messages exchanged in the network by other peers, so before broadcasting WANT-HAVEs to every connected peer, they will send an optimistic WANT-BLOCK to peers that have previously requested that content. If they are lucky, they will hit the content in a single WANT-BLOCK and receive the block in that same interaction, reducing the time to fetch the content to a single RTT.

Reduction in the numbers of messages exchange, saving bandwidth

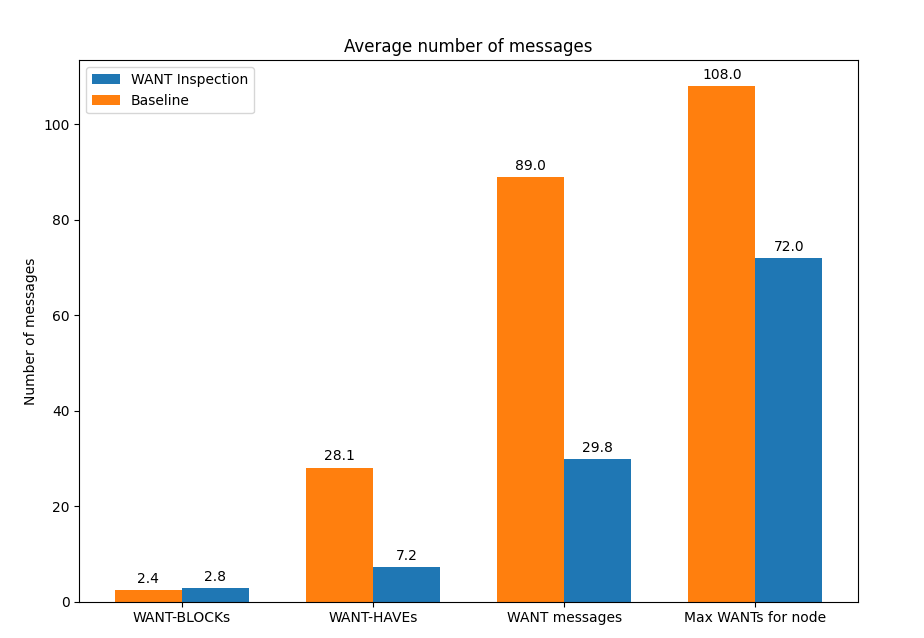

The use of message inspection has another interesting result apart from the time-to-fetch improvement for popular content: the number of control messages exchanged by Bitswap nodes is significantly reduced. Keeping a list of peers that have recently requested a specific CID in the peer-block registry allows the transmission of the optimistic WANT-BLOCK, eliminating the need to broadcast a WANT-HAVE to all our connected peers.

The average number of WANT messages exchanged is thus reduced by 33%, while the number of WANT-HAVEs is reduced by 75%. We get all of this at the cost of a slight increase in the number of WANT-BLOCKs exchanged of 7%.

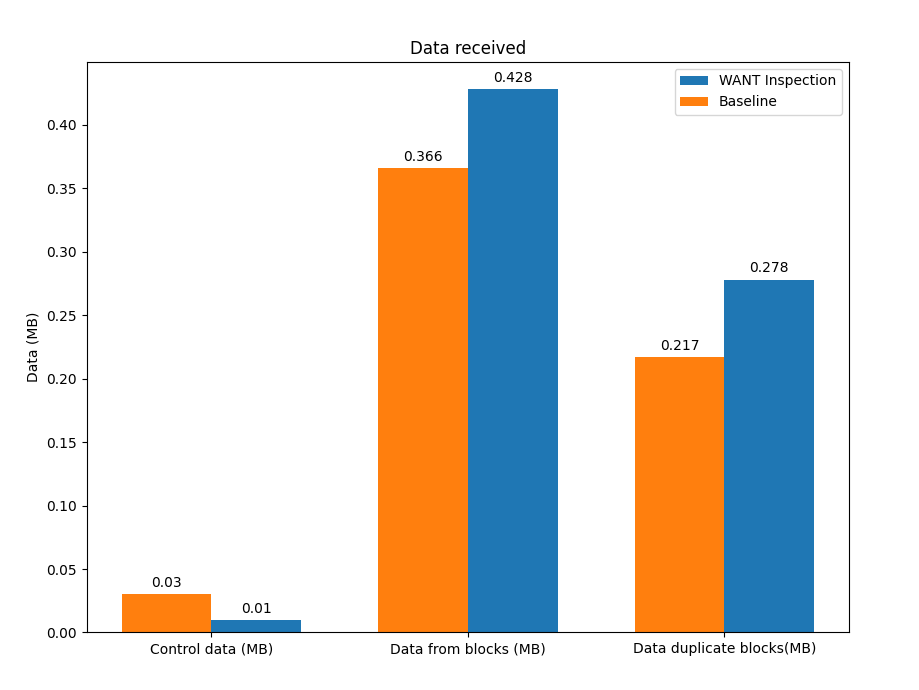

This improvement doesn’t come without a small tradeoff. The fact that we are sending an optimistic WANT-BLOCK to n peers from the peer-block registry that potentially have the content (in the default implementation n=3) means that the number of duplicate blocks exchanged in the network is slightly increased.

While in the vanilla Bitswap implementation a single WANT-BLOCK is sent to a peer that has answered that has the block, in our prototype we send three different WANT-BLOCK messages, and as we select the recipient peers from the peer-block registry, all of them will potentially have the block. The number of WANT-BLOCK messages to send to peers in the peer-block registry can be configured, so it could even be dynamically adapted to balance the tradeoff between savings in WANT messages and duplicates if we want to optimize for bandwidth use.

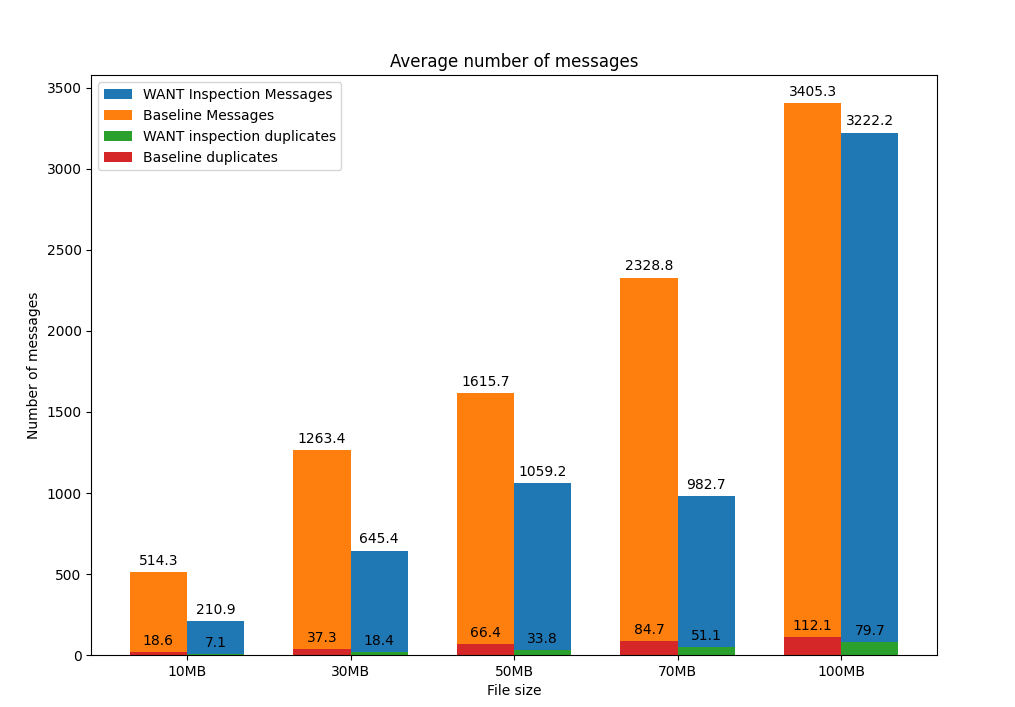

Playing with larger files

In all the aforementioned experiments we were using a file that would fit in a single block. We started wondering what the prototype’s impact would be if we exchanged larger files. We repeated the experiment with the same configuration but using different file sizes, and we obtained the results depicted below:

In addition to the reduction in the number of messages exchanged in the experiment (especially for small files), we inferred another interesting result. The use of the peer-block registry to perform smarter lookups of content doesn’t actually increase the number of duplicate blocks in the network, as we initially thought, but rather reduces it. In our initial experiments, we exchanged a single block in order to evaluate the performance improvement of the TTFB: each block exchanged in the WANT-BLOCK round sent by the peer-block registry generated two additional duplicate blocks. For larger files, the number of blocks exchanged is much greater, and knowing in advance which peers to request the content from prevents peers from polling the entire network, which consequently reduces the number of duplicate blocks generated in the file exchange.

Conclusions and Future Work

The implementation of this RFC stresses the effectiveness of using information about file-sharing, network events, or other overlaying protocols to drive faster content exchanges. For this RFC, just by listening to the content a node’s connected peers are requesting we can significantly reduce the time-to-fetch and the number of control messages exchanged in the network.

We are already considering several points of improvement for our current implementation to get the most out of our WANT message inspection mechanisms, including:

-

The use of the characteristic cache time of IPFS nodes and other heuristics to avoid sending WANT-BLOCK messages to peers that may have already garbage-collected the content we are looking for (as a way of cleaning and “garbage collecting” the information stored in the peer-block registry).

-

The dynamic configuration of the number of peers from the peer-block registry to whom to send WANT_BLOCK messages, so that according to the state of the peer-block registry, the specific application, the number of active connections, or the state of the network, we are able to perform smarter lookups either to make a more efficient use of bandwidth, or to minimize the time to fetch the content.

Additionally, we are exploring the combination of this RFC with other prototypes in progress to potentially achieve further improvements, one of which is the creation of Content Anchors that are designed to track all kinds of network intel to improve discovery of both static data (i.e. files) and dynamic data (e.g. PubSub Streams).

Stay tuned and do not hesitate to reach us out if you want to start contributing to this exciting line of work!